An Elegy for Education: In Pursuit of a Lost Spirit

I have been a teacher for a while, and I do not update as frequently as I did previously. Sometimes it makes you think why people update so rapidly and punctually, as I do not know it is more out of an obligation or a compulsive urge to speak, since ‘to speak’ and ‘ideas’ do not always, or should I say peradventure, align.

Being a new teacher is not exactly easy, and my pedagogies are only barely adequate, to put it in euphemism. But since I do not have many students, it is perhaps a place where classroom management isn’t exactly in demand. Nonetheless, I have taught for three months, and so far, I have kept the job.

Who is a teacher?

A teacher is, by the merit of its morphology, someone who teaches. In earlier times I believe that in Eton you had tutor, master, and headmaster. A tutor is ‘a guardian, custodian, keeper; a protector, defender’ (of their ward), and it is their ward (or commonly known as ‘pupil’) a tutor pledged to protect. Teaching is a regular profession, it requires some level of knowledge and some skills to convey them, but nothing more. Educator, on the other hand, perhaps is someone who educates. Again, by the merit of the corollary, we have to enquire: what is education?

Education, in its contemporary sense, thanks to bipartisan, statistics-empowered election, litigious by-products like Educate America Act, No Child Left Behind Act, or its ‘successors and heirs’, has been relegated to a series of consultancies and circuses, talking incessantly about ‘leadership’, ‘critical thinking’, and ‘lifelong learning’ but ultimately selling their packages of ‘standardised testing solution’, ‘digital examination service’ and ‘professional development for teachers’. It is of clinging cymbals and revolving doors, of self-importance, self-amplification, and self-indulgence. As for knowledge, it is always an optional extra.

Education is none of these to me, albeit I do shamefully teach standardised exams for my meagre income. As William Cory witfully articulated some centuries ago, education is about ‘making mental efforts under criticism’, and (in contemporary language) indicating assents and dissents properly, taking criticism even when they are harsh, gathering knowledge in a moment’s notice, and expressing them with clarity. When we first enter school, we learn how to write and read, and, even to a lesser extent, to speak and listen; if these skills were to be retained, we would learn how to study and express, but those skills are there, ultimately and solely for two purposes: to remember, and to live.

On Remembrance

On no account can I claim I am a person of literacy, or to any extent ‘educated’, but I indeed dare to claim I am consoled and humbled by some literatures.

Human is a lonely species; for a person covets the temperature of others but yearns freedom when he is warm. Whilst other creatures are begotten in dual pursuits of survival and reproduction, humans are inherently a dialectical contradiction, and it is the same for peasants and kings, even woe and weal might differ.

For thousands of years, or at least from the time we started to write, literatures are almost exclusively and repeatedly surrounded on certain topics, appeared in pairs of two opposing forces: encounter and departure, god(s) and devil, love and death, injustice and restoration, iniquities and rebellion, and the list goes on. Without any saying, one should acutely realise our reality has not change much since the time of those were written: most certainly in quantities, but not at all in qualities.

Humans are terribly lonely. One is ‘from earth to earth, from ashes to ashes, from dust to dust’. Surely one might buy certain amount of accompany with wealth, but one cannot buy the sense thereof. Especially in the face of death, we are – or I am – alone.

Knowing even wealth may disperse certain amount of loneliness with a disguised earnest heart, a person cannot allure himself to the conclusion that the same can be said about death. Human creates idols, either physically or virtually. Albeit one can be legitimately concerned about the affair of death when he is alive, more frequently we see horde of people are preoccupied by it. The fear of death, rather than death itself, overcomes the death itself and became the premier enemy of human species.

Literature, however, in its ground-breaking technology innovation of leaving some marks that persist after the death of their owners, has offered its kind solution in this: write something down, so lest when your perishable flesh collapses, your existence erased with them.

Despite the drastic change of the milieux in our worlds, our struggles do not change as much. They are continuing to set their own courses; Elon Musk, the South African slave owner, is in troubled waters because her daughter is transgender. Jesus wept when He heard his follower, Lazarus of Bethany, died. Although we are not matches for the ultrarich and Jesus, nor (hopefully) people uttering their death throes, we can sympathise with those torments in heart and ailments of flesh. Our experiences do not differ on these issues.

Would it be better, to offer some remedies to our future generations for some afflictions that are yet to come? For a teacher confined in his sad curriculum, such a question is probably frown upon. But when we contemplate and ruminate our roles, one shall realise, in his undertaking exists a duality: as a profession, with frequent meagre payment and support; as a vocation, with the responsibility to keep our vigilant watch so our generation to come will not fall in vain and dismay.

I am an ESL teacher in China, and a non-native speaker. Growing up in an underdeveloped region is synonymous with lack of education resources, where the top class of our best high school employs a lecture room to contain the sheer 130 students of theirs. Of course, I was not afforded with the best high school – or any high school. I was selectively marginalised as pariah to a rather low-performing high school, and they expelled me for voicing out my political concerns and for my mental distress.

Of course, I do not attempt to vindicate any of my inaction or accuse anyone, but as an erstwhile prodigy, with whom could I share my suffering and subsequent isolation? Despite I hardly regret the past at all, and eschew such attempt, I could not help but to imagine what would have happened had I known Jude the Obscure. What had happened on those virtuosi known to the world as Thomas Hardy and Richard Yates was entirely unbeknownst to me, thanks to the ill-prepared teachers. Of course, who could possibly lay blame on them?

We are in a philistine world where people in power are attempting to erase our brains and pasts, so they might be unassailable since nobody would know what words like ‘assail’ or ‘doublethink’ mean in the near future. We are living in a time where the word education, albeit no longer exclusively a word of privilege, is relegated to standardised examinations where things like characters, ideas, mental independence are casually omitted. On the contrary, education is not made more accessible, but rather cheaper, in terms of what we have to do and what we expect ourselves to be.

Education, in the end, is about conveying our common history and past to our next generation, it is about to enable people to read. I remember scarcely but poignantly how a migrant writer commented on his own situation after his emigration to France, how he was despised and lived in destitution, back-breaking exploiting jobs, and how he had to find solace in the shelter of literature.

Literature, meanwhile, not exclusively a by-product of suffering, predominately stems from such. There is a line I bear profound and enduring remembrance in the autobiography of Ningkun Wu, a doyen of erstwhile intelligentsia, returned to PR China upon its founding and was persecuted several times to the blink of death, in which he said in terse terms: ‘the protracted suffering was a life-sustaining gift’. Our lives are but a swing from boredom to suffering, and those who smile thought the tenebrous exude tremendous grace, if they will, to write the still rumination down.

Teenagers are usually vulnerable, which is of my view, a natural result of our industrialised and streamlined education. Humans are treated like poultry and cattle with their souls detested. One cannot pretentiously and sanctimoniously lament the death of civility and decency without subject himself to an even harsher censure. Our generation fails to assume the undertaking to impart, or even assume, characters and moral sobriety to those who are demanded to have. The solution is right there, but it seems our noise are too loud to deafen the prophets.

We have a rich treasure of consolation that lies in our past, a refuge ourselves refuse to listen to. ‘The voice I hear this passing night was heard / In ancient days by emperor and clown’, but our ostensible education belies the heritage of our predecessors, moreover, sadly replaced the truth. How can we survive without acquainting those who toiled the share same as us? At least I could not have done so.

On Expression

Words are oft-times meaningless. From my experience as an Order Coordinator (glorified parcel-tracker) in the past, most of my work was about talking to illiterates in plainest language possible. The illiteracy does not come from the lack of education (nor does education help with it), but rather a corruption in our mindset, a mindset where articulation is discouraged, or even forbidden. When we start to neglect expression as our quintessential part, our humanity cracks a bit.

‘Whatever’, it is a reply I am inundated with in my life and by with I am haunted. We, as an intellectual species, pass our memories and thoughts to our next generation with words and marks. When we willingly forfeit our abilities, our rights to think and to express, we are devouring our humanities away. Each time we allow others to alter our memory, to master over it, we sow a vacuum of truth, and lies will soon fill the vacuum. As lie grows louder, it hinders truth, and it becomes so loud that we cannot even accept the truth even we hear it.

I live in a milieu where thinking itself is a crime. We punish those who think and speak, and for those obey and oblige we reward with economic growth. It is the modus operandi of the regime after the Reform and Opening-Up. Our interdict on thinking embodies itself upon the Tian’anmen Massacre, where a synchronised, well-coordinated mass murder took place all over the countries, and the names of the deceased, or even the death toll, remain unbeknown to us. A generation, our generation, attempted to express at the expense of their lives.

In this milieu, firstly we were complacent about the forfeiture of expression. Some of us thought it was okay, and it was all about the rapid economic growth and growing disparity, whilst the rest of us worked in abysmal condition in the hope they could afford the tuition fees of their children; then, we faced the consequences: mass murders, massacre, summarily execution, open and overt disregard to the judiciary, and an internal crackdown expense higher than military one. Now, I am living in a society where the only opinion we dare to voice is to concur the ever-updating, ambiguous, and self-contradicting talking points of our leadership, and we are censured for not praising loud enough.

Expression is the human way to combat with death. I have worked in a restaurant at different capacities for about 24 months, and despite the physical hardship and meagre income, I found my life there generally abhorrent: my colleagues were a multitude of people, and most of them were capable of work-related communication, but it seems they were not able to express with clarity when it came to themselves. Some lamented the ‘lack of effort’ during school age, but never did they complain about any systemic issue. All they blame, as everyone else has placed their blame on them, is themselves.

Of course, one can well suspect that the schooling intends to indoctrinate someone, mould someone according to the needs of the society. But fundamentally, whilst double-entry bookkeeping is a skill that serves your survival subsistence, word represents a person, it conveys the idea and identity of a person. Of course, there are numerous ways to ensure the longevity of a person, however literature holds its place with its time-honoured tradition.

In my teaching, I stress all questions, after-class, should only be sent via email, a method not so commonly used in China. Expression serves not only as an external, communicative tool, but also as an internal, introspective mean for a person. I used to tutor a medical student, and what he wrote was absolutely incomprehensible. Despite the uncommon and glamourous vocabulary, paragraphs carried insignificant amount of coherence, and arguments were ill-prepared.

In English teaching, one must value L1 influence, this is a term of the systematic implication towards one’s English command. However, it is not only language itself at fault, but also the culture underlies it. Our cultures vary, but they all belie a real issue in our respective milieux: the silence of humanity, and the noise to swap it, substitute it with consumerism. It seems our generation is growingly incompetent: we now offer ‘creative writing’ classes, we offer a step-by-step guide for students, our next generation, to become copywriters for corporates.

We ended up with forceful writing, terse writing, impactful writing, all sorts of employable writing. We ended up with writing reports where pictures depicting a collection of smart-dressed, white collar workers are smiling like they are high on weed.

What sort of audience we are expecting, those who unwilling to read anything more than four lines? The question should be phrased differently: what sort of audience we are cultivating?

One would helplessly lament the loss of our civilisation on the wreckage of ‘bruhs’ and ‘based’, of ‘l’ and ‘w’s. How can we have any meaningful conversation where people are wittingly and volitionally forfeit their ability to perceive, think, and to criticise for themselves? How, we, as a society, or a humanity in common, forest any hope on these debris?

Our generation is facing a massive existential crisis: where everyone is busy speaking but not in words; everyone is busy reading the text which reflects no thinking; everybody is criticising without ruminating; everybody is listening but without meaning. By building an entire generation on the premises of full employment, shareholders’ dividend, actuarial sciences, and STEM education, we seal our fate as a species without strength to face its past nor hope for its future.

In the end, we are not educating, as our education belies its true meaning. Education means not only to cultivate literacy, and definitely not for the glamour of those prestigious degrees, but for cultivating the seed of hope, so lest our next generation feel despaired when the world is dampened with absurdity.

We reap what we sow. If, for the remaining educators, if there is any remain, they should salvage the capsized ship by telling our children right from wrong. We should tell them to remember in antiquity someone suffered like they do, and in the future our hope can be stored.

Everything we are facing now, by the merit of its nature, must have been experienced by people precede us. When Lazarus died under that table, we must have felt some consolation from the singing of angel; when we are on the hype of our success, the King of Solomon reminds us not to trumpet; but moreover, we are not alone. In the face of this all-eroding and all-invasive loneliness called death, we have proudly withstood.

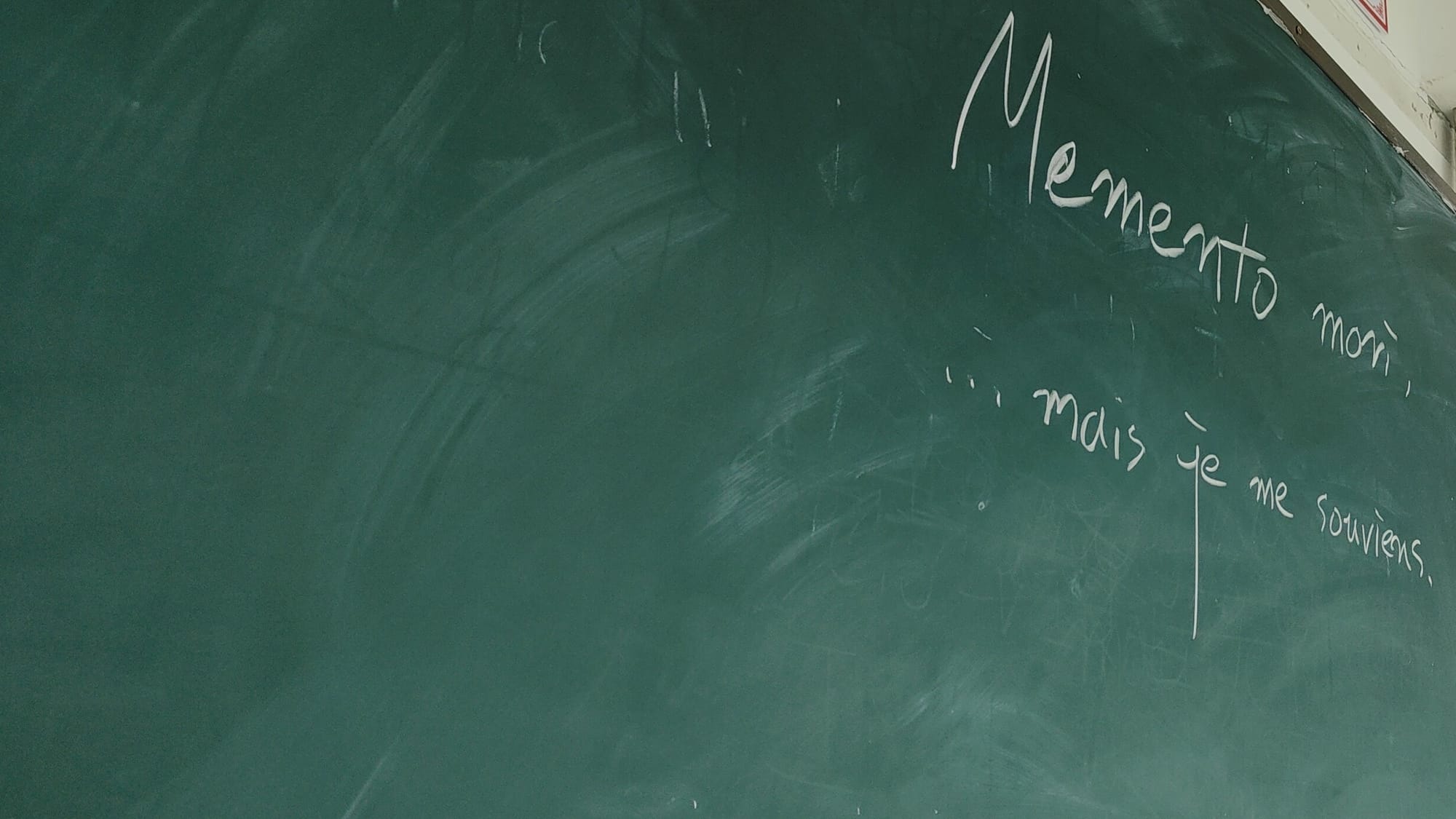

Everyone dies, but I remember. With our remembrance, the length of our thoughts supersedes the one of death.