From Ward Confined to the Liberated Kingdom

The Locked Room

It was always like that, as I have known it for too many times, a ceiling of pure white and light, designed to sensory overwhelm you. The humming and flickering sound of the ballast in the florescent lamp maintains an oppressive and persistent hum. If there’s someone who would ask me for what it looks like, it would be the answer. Dull, boring, stimulating in an annoying way. That was the room where I spent half of my life, and the other half in a room alike.

I was deprived. To be precise, I was given only whitelisted items. Cosmetics and shampoos are locked, my precious Lamy 2000 was seized from me, along with the Pelikan M200 which resembles an engraved memory. My rosary, a gift from Jerome from Australia, was also taken away. So bluntly, from me, from a social existence to an animal which is not entitled to human dignity. I still remember the toilet paper I was allowed to use – it felt like sandpaper and recycled a thousand times already.

A quarter became long. From 4:45 am there was echoes from the empty corridor, sounds of drawing blood and the beep of PDA executing medical order; At 6 am everyone was forced to wake up; nursing workers unruly banging on our beds, random Cantopop. We were cast into the ‘living room’ like a bunch of ducks, comprised of nothing but bare chairs like a half-decorated, aged waiting room in a train station. It was the entirety of our lives – transverse between two rooms, every single day, like a swing.

It was locked. The entire building is. Each door and room are guarded, empty rooms (at least when they are supposed to be empty) are locked. Open doors are always guarded, every entrance and egress were counted. We lived in a cage, a cage that claims capable of fixing us.

A quarter, erstwhile transient, become very long. Before going in, you would never know that the corridor clock blinks for one second, and it takes 60 blinks to move one minute; a minute multiplied by fifteen equates to a quarter, and about five quarters you would have your mundane food of one dishes and douse rice. This is a place where people walk slower, think slower, and speak slower. This is a place where people stopped being a community, but individuals crawling together. I can vividly recall the smell of human, nearly fifty individuals, who have not showered, caged in a room with little ventilation. I can never forget the filthy air I was forced to be put in. After all, comfort is never the focus. Rules, institutionalisation, and orders are.

By the river of Babylon, there we sat, yes, we wept, when we remembered Zion. Our rosaries, dignity, gender expressions, and interests were stripped, those things we spent much to build. We were forced to pee under watch, to shit under watch, and to do everything in the stinking restroom under watch – which opens only one, and others closed seemingly for our humiliation.

Exile within the Walls

‘O, Lord, do you work wonders for the dead, or do the departed spirits rise up to praise you? Is your loyal love told in the grave, or your faithfulness in the underworld?... But as for me, I cry for help to you, O Yahweh, and in the morning my prayers come before you – why do you reject my soul, O Yahweh’? Lord, does your shining continues to bright for us on the bleak celling?

In Isaiah 56, God gave us a clear, unambiguous answer: ‘and I will give them a monument and a name in my house and within my walls, better than sons and daughters; I will give him an everlasting name that shall not be cut off’. In a world where eunuchs and other marginalised people were rejected, God, even in the First Testament, has promised them a ‘name and memorial that are better than the ones of sons and daughters’. In Deut 23:1, the previous commandment was clear about it: those people are expelled from the ‘assembly of Yahweh’.

Aren’t those people in exile, being cast away from the society and the ‘assembly of God’? Just like Matthew Shepard, who has been beaten to death by his peers just because he was gay. Confused, trembled, Matthew was tied to a fence and left to death there. Did God reveal Himself to him, in the final hours of his tragically transient life? No. At that moment, he became Jesus. Like Jesus, he was beaten, left outside Jerusalem, and died in excruciating pain. Like Jesus, he was wondering where his salvation is, and why he was cold-heartedly abandoned.

By Jesus, God entered our world, thus our sufferings. By Jesus, God suffers with us – that he hears his children’s cry. Maranatha, Lord, Messiah! When Simeon implores the Spirit for the Saviour, he implores God enter our sufferings and our joys. I can remember when I was staring the walls of my room, I couldn’t see God. No, in that moment, God enters me.

In Richard Wurmbrand gave us an answer – where he told us during the three years he was solitarily confined as an underground leader, he couldn’t see any visible light, nor talk or hear the voice of anyone; but in the silence he heard the voice of God – or the silence itself is the voice of God. He mentioned the silence could be his offering to God, a path to his sanctification.

In a psych ward which is rosary-less, I remembered how to pray – how to pray with a paper. I remembered the lost prayer, the Memorare, piece by piece. I now remembered, just as I always remember. A girl can be deprived of her rosary, but never of her heart – her heart for the fallen peers of hers.

Human, and Lesser Human

When I was later working on the oral history project, I found a same depiction of two people in the ward. I knew them faintly, to an extent I must confess that I remember them faintly. ‘Lack of self-awareness’, ‘exaggerated thoughts’. Now the doctors are using their trust and full confessions as the weapons against them. Are we humans worthy of being seen? If we are, O Lord, why aren’t we heard and respected?

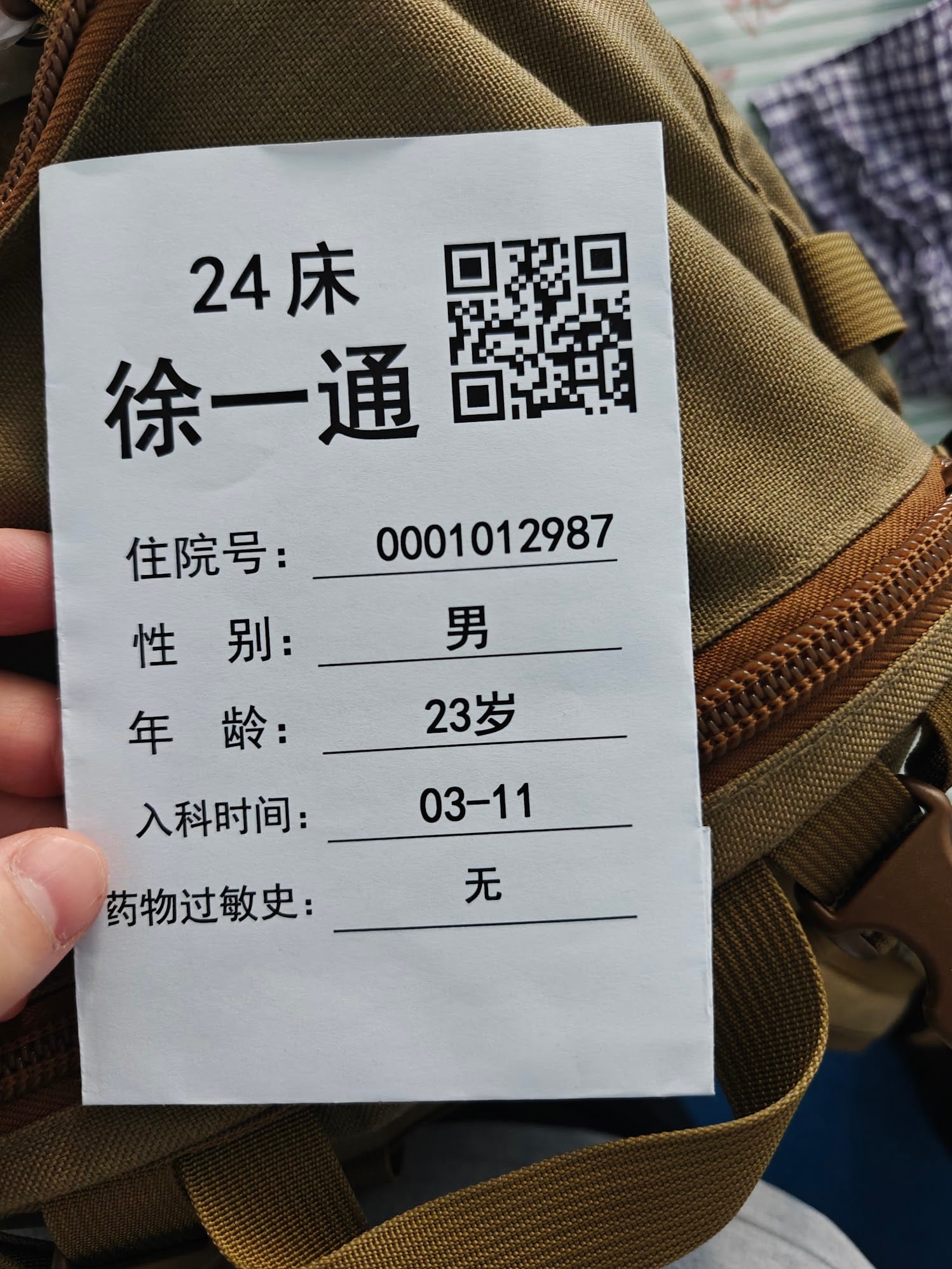

We are not animals being managed, we are human – and we shan’t be lesser human just for our temporary wound. We are given an egg every morning, the same egg, for a time of infinite length. We are institutionalised as nouns and numbers. However, there’s no lesser human in the eyes of our Lord.

The Liberated Kingdom

We speak of the Kingdom of God not as a place far off, but as a presence that begins here, among the locked, the broken, the institutionalised. If the Kingdom of God is among us, then it must be capable of entering these sealed rooms and bitter memories. If not, it is no kingdom worth hoping for.

And it is here—yes, here—that we find the paradox of liberation. It does not come with open doors, but with opened hearts. It does not always come with freedom, but it always comes with truth. That truth may be unbearable. It may be that your rosary is still locked in a drawer, your gender still denied, your prayer still uttered alone. But that does not unmake the Kingdom. The Kingdom is proclaimed precisely in these realities, not in spite of them.

I am often asked if I believe in healing. My answer is: I do, but not as the world does. Healing is not forgetting. Healing is remembering rightly. And remembrance, as the Psalmist teaches, is divine: “You have kept count of my tossings; put my tears in your bottle. Are they not in your book?” (Psalm 56:8).

My tears, too, are counted.

So I write this not to explain, nor to forgive what ought not to be forgiven, but to insist: we were there. We, the forgotten, the confined, the disdained. We lived and hurt and sang and prayed and wrote. We were humiliated but not erased. We were broken but not lost. We were imprisoned but not silenced. And though our blood cried out from locked wards rather than battlefields, our cry is not unheard.

And so, to the broken girl who prayed in silence, to the friend who forgot her own name, to the man who never spoke a word again after being tied down—I offer this page.

This is your stone. This is your name. It shall not be cut off.

Amen.